Ah yes, cancel culture. The bane of an online conservative’s existence and the greatest weapon of internet progressives.

The dawn of cancel culture came in 2020, during the campaign season and the COVID-19 pandemic. As both sides have turned to the extremes, both accusations of people being canceled and actual cases of cancellation have flown in both directions, yet it begs the question:

Which side is correct on the issue?

I don’t think that’s the question that should be asked; rather, I think this one is a more suitable one:

I don’t really think so. First, I’d like to start with what progressives get wrong about cancel culture.

Oftentimes, cancel culture is used when someone online is simply expressing their own opinions. Therefore, it’s an unjustified infringement of people’s 1st Amendment rights in those cases. If you state a vaguely conservative-sounding statement and it makes airwaves around social media, chances are eventually someone will probably try to cancel you.

There are occasionally cases where there was legitimately terrible stuff said by the victim of the cancellation attempt, but even then, there’s still another issue at hand: they said that years ago. Sometimes even decades ago. And as many people know all too well, people’s views can change considerably over a decade.

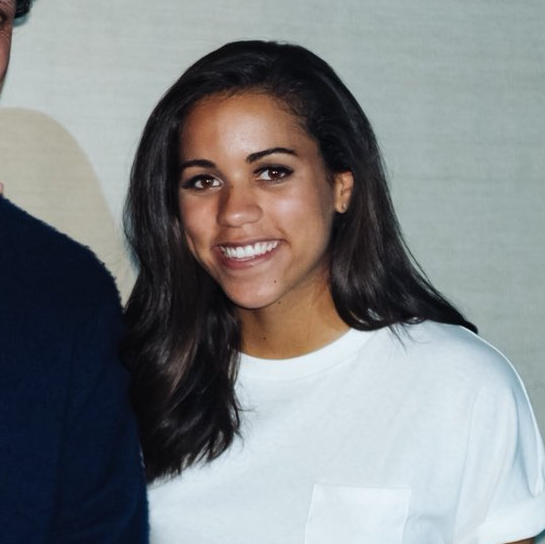

In one case, back in March 2021, Alexi McCammond, a journalist who was 27 years old at the time, was hired as the new editor-in-chief of Teen Vogue, which is quite prestigious for someone her age. Everything was ready for her to take her post. However, her soon-to-be colleagues came across deleted posts on her X (formerly known as Twitter) account, expressing seriously homophobic and anti-Asian sentiments. Because of that, they demanded that Teen Vogue’s parent company, Condé Nast, stop the process of hiring her. Condé Nast initially refused, but advertisers threatened to pull support, so she eventually resigned.

Now, here’s the problem with this case. The heinous things she said online were posted in 2011, a decade before she was brought on by Teen Vogue. And since she was 27 in 2021, do you know what that means?

That’s right–she was 17 years old when she said those things. She was a minor. And her career was permanently tarnished because of things she said when she was a junior in high school. Not only that, she had acknowledged the posts two years previously, in 2019, and had apologized for what she said in the past, which she no longer believed in.

To put things into perspective, that’s like firing someone from their job for a minor work rule infringement a decade before, as they’re finally admitting it to their boss in a passing conversation. It’s ridiculous, right?

Some conservatives online will point to a case like McCammond’s and call it “woke leftist degeneracy” or whatever insulting words towards liberals they can possibly combine. However, they’re also wrong about cancel culture. Why is that? There are a couple of reasons.

First, there are cases where the “victim” says terrible stuff, and when they’re rightfully criticized for it, they just claim they’re being canceled by liberals, almost as if it suddenly makes them immune from fair criticism, which it doesn’t. You have to be a toddler to think that it does.

However, that’s fairly minor when it comes to the second reason. What is that reason?

Conservatives often unknowingly partake in cancellations themselves. Let’s take the case of President Donald Trump. In a speech during his 2020 reelection campaign, he said the following on cancel culture: “One of their political weapons is ‘cancel culture’—driving people from their jobs, shaming dissenters, and demanding total submission from anyone who disagrees. This is the very definition of totalitarianism, and it is completely alien to our culture and our values, and it has absolutely no place in the United States of America.”

You know, Mr. President-elect, I would have to agree with you there—oh wait, what? He partook in canceling before he spoke against it.

What? Are you serious?

Yes, my friend, he did and, arguably, still partakes in it. Let’s take a look at a few cases of him participating in cancel culture, shall we?

During the 2012 presidential campaign season, Trump called on Touré, an African-American journalist, to resign from the MSNBC show “The Cycle” after uttering a version of the N-word while attempting to argue that then former Governor Mitt Romney of Massachusetts, the Republican nominee, who Trump supported (ironic!), was attempting to discreetly use racially coded messaging to make incumbent President Barack Obama seem frightening.

In April 2015, he called for one of National Review’s senior editors, who is a conservative, to resign after calling out Trump for “tweeting like a 14-year-old girl,” while responding to another conservative writer’s criticism of Trump, in which that writer called the future president a clown. Trump also suggested that Bret Baier, a Fox News anchor, should stop hosting that senior editor on his own show.

The last case of him participating in cancel culture took place in May 2020 and is, in my opinion, the most serious case of it. A day after Twitter put a fact-check link on one of his posts going after mail-in voting, he just outright threatened to shut down social media companies. He stated, “Republicans feel that social media platforms totally silence conservative voices. We will strongly regulate or close them down before we can ever allow this to happen.”

Should I remind you he was the President of the United States at the time? There are serious implications when the most powerful man in the most powerful country in the world says something like that.

So in the end, I do really think that progressives, liberals, and conservatives are all wrong about cancel culture. It’s a blatant violation of our cherished First Amendment principles I am proud to say we champion all across the globe. However, as I’ve established, all sides of the political spectrum partake in it extensively, even if they’re unknowingly doing it. And needless to say, cancel culture is a cancer on America’s soul that needs to be cut off before it can fester and metastasize.