Are Students Learning?

In the past years, learning has changed in unpredictable ways and will probably continue to evolve.

March 29, 2022

It is no secret that schools and learning worldwide have significantly changed in the past three years. Students of all ages are forced to face this new type of learning: COVID learning. While schools seem to be on the trek back to “normal”, are students really learning?

Back in March of 2020 when the world started going into lockdown, it is doubtful that schools and educators could have predicted the impact COVID-19 would have on worldwide school systems. The phrase “remote learning” is enough to trigger memories of the seemingly never ending Zoom meetings, hours of time spent looking at the same computer screen, social deprivation on all accounts, and the abundant amount of stress placed on students trying to get by, parents trying to balance work and their children at home, and school administrators attempting to make the most of a difficult situation.

In previous years, most students never had to think twice about school. We just went. But with the new changes we see today, learning as we knew it has evolved into something more complex than before.

Acquiring long-term knowledge is a complex process to begin with. Short term to long term knowledge is an effortful process, meaning that the transition requires conscious effort to obtain—such as attention, rehearsal, and repetition. Hence the phrase, “practice makes perfect.”

Learning is also tied to multiple social contexts: interpersonal relationships, emotional well-being, and social-emotional development. Interpersonal relationships and communication are critical to the learning process and overall development of students; emotional well-being additionally plays an important role in the learning process. Each factor is connected in some way, affecting the others if one is changed.

So when social access is altered (or obliterated), it affects the students’ emotional well-being and in turn their educational performance. COVID-19 successfully cut all ties to society for a period of time. And when a person’s social environment changes, it challenges the brain’s sense of stability.

Unfortunately this swarm of emotional stimuli has been in effect for years now. Learning can be a difficult process to begin with, and adding social and emotional obstacles certainly does not help. When comparing the 2019 MCAS results to the 2021 scores, there are some noticeable differences:

There has been an evident decrease in the percentage of scores meeting state expectations (green) from 2019 to 2021, and a slight increase in scores not meeting expectations (red). In 2019, the percentage of students meeting expectations ranged from 40% to 48%. However in 2021, the percentage of students meeting expectations declined to a range of 34.2% to 45.2%. In a similar way, the percentage of students not meeting expectations in 2019 were between 8% and 14%, whereas the number of students in 2021 who did not meet expectations increased to between 9.1% and 22.2%.

Additionally, when looking at the ELA average score changes (table), you can see that there were more negative changes than positive in the tests. The table displays the average scaled scores (by grade) in 2019 and 2021, and the change in scores between the two years. The greatest regression was found in the eighth grade results, with a change of -5.2; the least regressive score change being +1.1 in the tenth grade.

These changes could be due to a variety of factors and outside influences, making it difficult to pinpoint one specific cause. However, the bottom-line is that COVID-19 has impacted people around the world, including the school systems. In the past years, learning has changed in unpredictable ways and will probably continue to evolve.

As this happens, implementing the foundations of learning into school systems can help maintain a positive learning environment for students amidst the changing times.

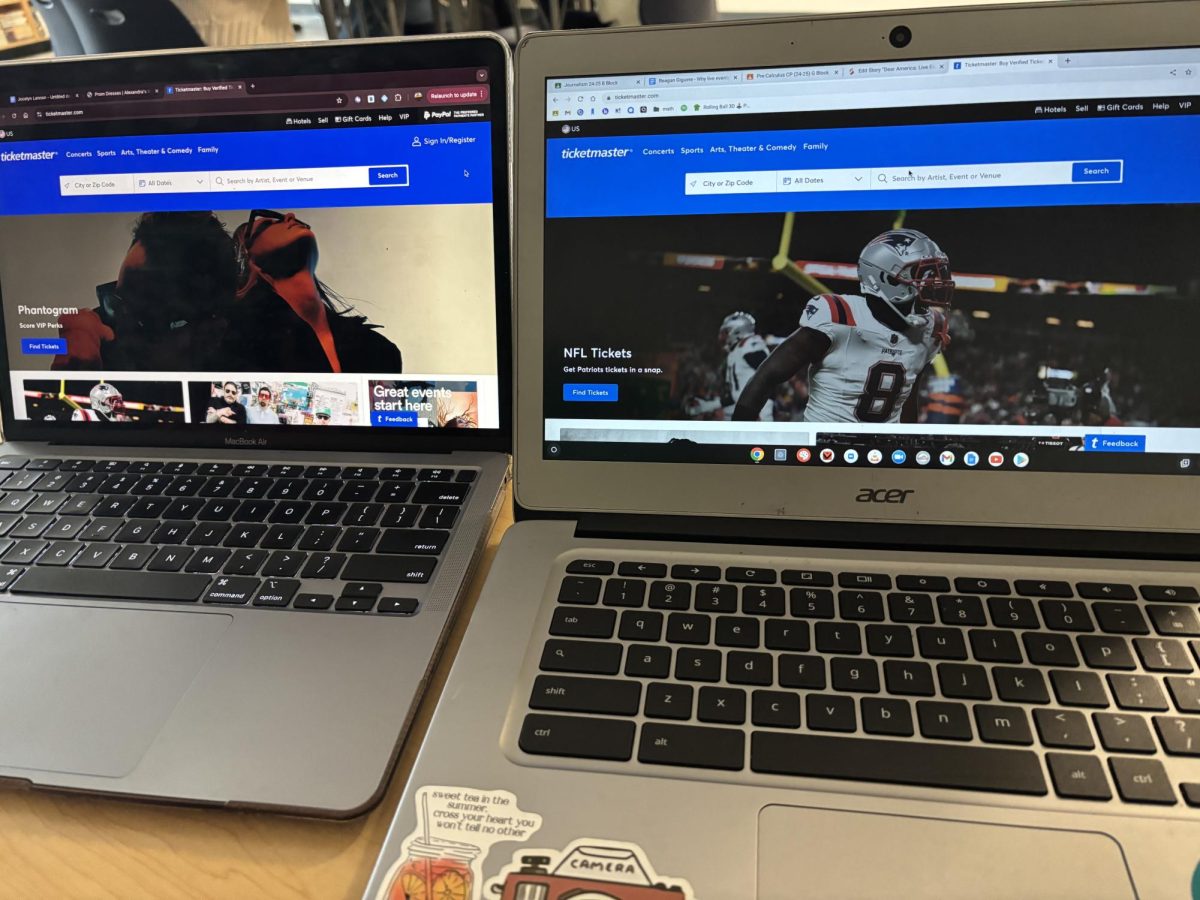

Knowing how students learn best can enhance and possibly restore some of the learning that has been lost over the years. Bridging the gap between the present and the years of coursework that was pushed under the rug, seems to be an overarching challenge. However, students are capable of higher level thinking in some knowledge domains more than others. If students are in a familiar knowledge environment, they will be more successful learning new material built off the foundations of what they already know. Instead of rushing into new chapter units, teachers can work towards building a cumulative curriculum that connects the pieces of their classes together.

One teaching tip the American Psychological Association(APA) recommends is breaking tasks into smaller and more meaningful parts for students to digest easily. Rather than assigning that huge end of the chapter test, maybe consider a more intimate group project. This way students can work with their peers, participate in a hands-on manner and in the end, learn in a memorable way (instead of cramming a bunch of information the night before a big test).

Lastly, creativity can inspire learning. Implementing creativity, invention, and discovery into the classwork brings a new perspective to something that can seem mundane for kids. Promoting questioning, challenges and problem solving, and prompting unique connections, new ideas and options, are all some ways to branch out from the basic classroom lecture or simple worksheet, but most importantly: engaging students in new ways of thinking.

As school systems and teaching continue to evolve, incorporating some of these key teaching techniques into regular curriculum can help students navigate through this ever changing learning environment.